For several months I’ve been meaning to watch Sara Colangelo’s second feature. (I was quite impressed with her first from 2014, Little Accidents.)

Perhaps I delayed watching The Kindergarten Teacher because, more than most movies, I knew this one would require my focus; after all, examining depictions of educators in popular culture is one of my major research areas.

What I discovered–not unexpectedly–is that this is a particularly complex film.

In my research on teachers in the movies, I have identified a genre called The Good Teacher Movie in which main characters are identified by a set of traits that remain remarkably consistent over time, a pattern I call The Hollywood Model.

The defining traits of these good teachers are as follows: they are outsiders; they become involved with their students’ welfare on a personal level; they learn important lessons from their students, which makes learning reciprocal; they often have problems with administrators and conflicts with other teachers; they personalize the curriculum to meet the needs of students; and, many of them (especially males) have a ready sense of humor.

There are also important revisionist films, such as Election (1999), Half Nelson, (2006) and Detachment (2012), that present educators who fit the characteristics of the good teacher according to The Hollywood Model, but these movies complicate the main characters by writing them with all-too-human foibles of one sort or another.

I’ve also written about “bad teachers,” characters typified by their own sets of traits organized around maintaining order and discipline at all costs or focusing solely on learning outcomes (mostly defined through standardized tests) or acting in unethical ways that compromise students (either through sexual misconduct or misusing their intellectual property).

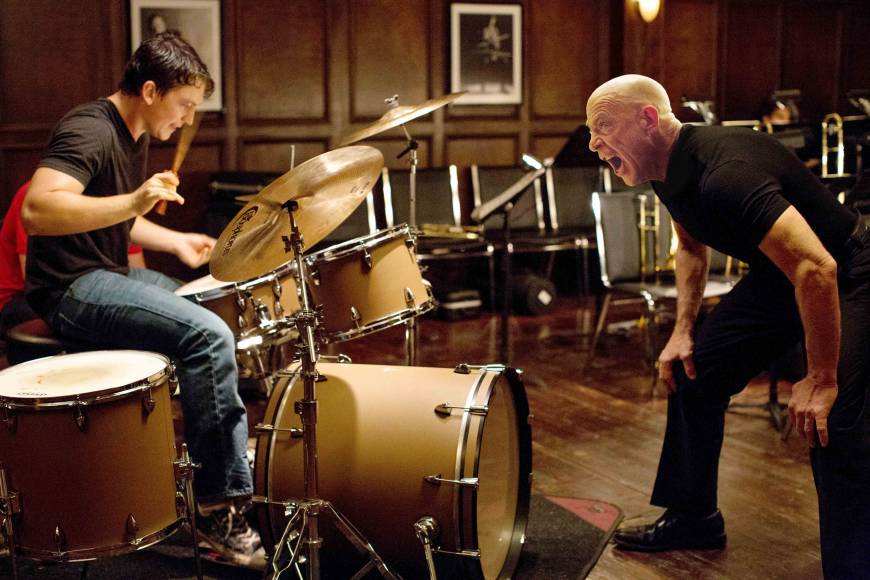

It would be reductive to try to force The Kindergarten Teacher into either of these dichotomized modes–“good” or “bad.” Instead, this film presents a more complex argument along the lines of what I’ve seen in Whiplash (2014), Damien Chazelle’s magnificent film.

This is what I wrote about Whiplash in the latest edition of The Hollywood Curriculum: Teacher in the Movies (pages 81-82):

On the surface, Fletcher (J.K. Simmons in an Ocsar-winning performance) is clearly a bad teacher who berates students mercilessly and even bullies one into committing suicide at a fiercely competitive conservatory. The story focuses on a talented drummer who falls under the sway of Fletcher and suffers for it. The entire film leading up to the climax seems to suggest that Flether’s techniques are inhumane (they are) and counterproductive (they seem to be) only to be contradicted in the final scene. The message delivered at the end of the film is that only by pushing students to the brink can some of them reach their highest potential. Is it worth it? The answer to that question will come from individual viewers, who are unlikely to reach a consensus. Is Fletcher unkind? Yes. Are his methods effective? Sometimes. Is he a bad teacher? I don’t know, which is one reason among many this film is brilliant.

The Kindergarten Teacher constructs an ending that evokes the same sort of ambiguity as Whiplash–if viewers choose to read it that way. Lisa Spinelli (Maggie Gyllenhaal) is focused on developing Jimmy Roy’s (Parker Sevak) talent while no one else has either recognized it or taken his poetry seriously.

[SPOILER ALERT] The end of The Kindergarten Teacher suggests that the teacher’s fears that the world will erase Jimmy are coming true. The boy sits in the front of a police car as, presumably, his teacher has been arrested for kidnapping, and he says, “I have a poem” while there is no longer anyone there to write it down. Clearly, Spinelli is obsessed with the young boy because of his talent and acts in ways that are definitely out of bounds legally and ethically. Yet, the film is more complex than to suggest with complete clarity that Jimmy is better off without her.

It is possible for two competing ideas to both be true. I love films that make me think and look forward to see what Sara Colangelo brings to the screen next.

I too love when movies make me think and complicate the conventional knowledge that most people blindly accept. People want to rest assured in the appearance of “children being children.” That way, the hierarchy is in tact and children aren’t trying to topple or subvert the system in which they know nothing and adults know it all. Adults can use the excuse of how hard it is to manage their complicated lives to keep from questioning knowledge.

So when an adult takes an interest in the talent of a child, it is looked at in one of two ways: the mentor/nurturing figure—or that image can quickly change to the inappropriate person. Something must be awry if she likes spending so much time with a child, who knows nothing and can do nothing of consequence. This takes everyone out of their “appropriate” roles.

As you state, Lisa Spinelli takes inappropriate steps to preserve Jimmy’s talents. But making a final assessment of her actions is not that simple, as the ending indicates. The dire circumstances she believes herself to be in—fighting for art, if you will—is not just her imagination. Dichotomous thinking about what children and adults are capable of artistically and intellectually push her to act how she does.

Lisa’s relationships with her own children, I think, are very telling. It seems that she feels that she has already “lost” them to a culture that hammers out creativity and individuality, and she does not want that liberty to be taken away from a student in whom she sees an extraordinary amount of potentional to go against the deadening fate most fall into.

Excellent points, Chad. I agree completely about Lisa’s relationship with her own children, especially, and think this is conveyed in the film perfectly with great strength but also economy!

I felt like it got a little sexual when she showered and it lost me there a bit. Was I just reading into the shower?

You know, I actually did not see that as sexual. It was clear from the very beginning of the film that the teacher is very sensual in the classroom. I was discussing with someone this morning via text about how her exposed breast (in the “coitus interruptus scene”) serves as a maternal symbol (she does leave her husband on the sofa to go answer the call from the student), and her body is not revealed much when she has sex with her poetry teacher. This is a big contrast to the final sequence. While she crosses the line in many ways, I feel that she reserves the sensual aspects of her being for her students and for “art” but contains, or at least minimizes, her sexuality overall in favor of the maternal. The fact that her kids don’t give her much space to express it with them leads her to an outsized expression of the maternal and the sensual in the classroom. Unlike, for example, Blue Car, where the teacher is a predator who grooms a vulnerable high school student (also through encouraging her writing) into one of the most uncomfortable coerced sex scenes I recall. Of course, maybe I am projecting…

oh interesting, I see that. I’m such a simpleton. thank goodness I don’t have to write scripts. (ugh)

Ha! Well, the maternal breast was actually Elizabeth Currin’s insight! She teaches the film to education students, has discussed this film in class with them, and has been writing about educators and popular culture for a few years. The metaphor of teacher as a maternal figure is a common thread in education literature, however, so we are primed for this discussion in ways that even magnificent television writers are not. This is exactly why we need to work together to develop a revisionist series focused on a teacher–something like the Danish series Rita but even better!!!