Here’s a special treat for Triad viewers.

a/perture cinema will screen Cagney Gentry’s debut feature Harvest on Monday, June 27 at 7:30 p.m. in the Made in the Triad film series. The screening is a partnership of a/perture and the New Winston Museum and is sponsored by the Piedmont Triad Film Commission. Ticket and series information is available here.

I’m a longtime fan of Cagney Gentry, as a person and as an artist, and we’ve had many conversations over the years about film. Naturally, I wanted to talk with him after I had a chance to take a look at Harvest.

You can eavesdrop.

Mary: Where did the idea for Harvest come from and how did the process unfold for you to develop it?

Cagney: The idea originated from, as I remember it now (it was almost seven years ago!), two simultaneous forces. One was a true story about a man from deep in a hollow up in the Blue Ridge who was known for his ability to find wild ginseng and who was found dead after making deals for ginseng that he had not yet delivered. The official story was suicide; the locals suspect he was killed. The second inspiration was working with a man named Paul Hodges in a cherry orchard up near Fancy Gap. This was hard work and probably work he was no longer suited for, yet he still did it. He did it with this sort of methodically constant pace, and he had to stop and rest (smoke), but then he would go back at it. He had the same thing for lunch every day, and he mostly wore the same outfit every day (not the same exact but the same-looking outfit). He was a man steeped in routine.

So, it occurred to me that I’d like to make a film about the routine of life and how that routine gives us comfort until it is disrupted by the forces around us. And, certainly, the forces of nature, on some scale, instinctually act to disrupt our routines. So, Harvest, became the story of an aging man who finds a confluence of forces acting against his routine at this very pivotal moment in his life.

Mary: I want to talk a bit about pace and place. First place because you do such a beautiful job with the space, interiors and exteriors. Do you have a special connection to the location? How did you find it? What does it say about our main character, Hank?

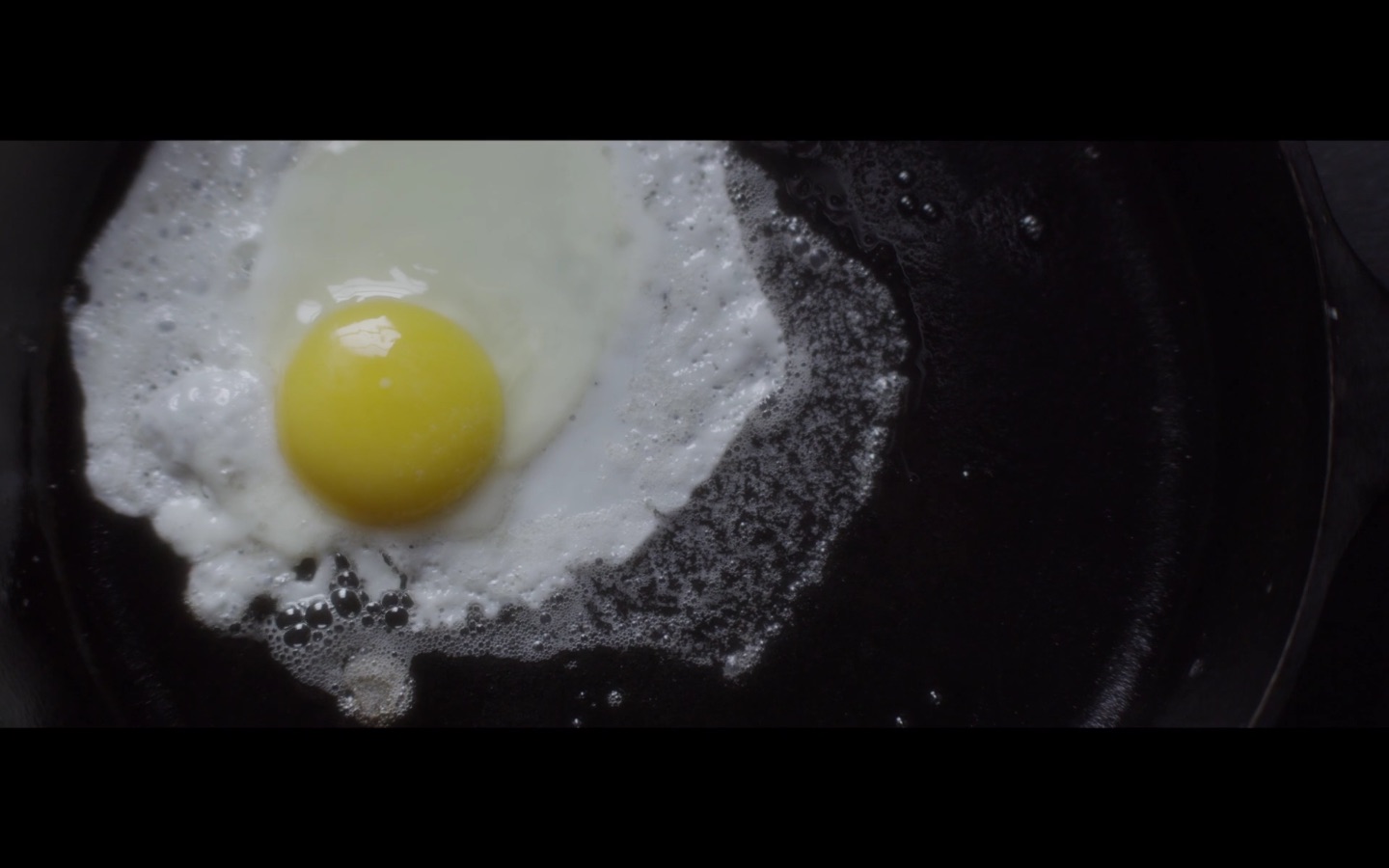

Cagney: I had no special connection to the physical location, at the time (I do now!). I did see this place several years before because it is in my hometown, not far from where I went to high school. It is a beautiful farm, uninhabited, right at the foot of Rendezvous Mountain in Purlear, North Carolina. With the help of the film commission in Wilkes County and the extreme benevolence of the Rector family who owned the farm, we were able to film in the location. We stripped carpet up, removed furniture, re-furnished, and placed every item you see in the film. Even the oven was altered because it was not a working oven. The eggs were cooked on a hot plate.

The location was perfect to me. I can remember being told by people from that area that there were clearings in the foothills that were most certainly natural clearings, not manmade by timber-cutting and plow, but clearings that most likely hosted generations of Americans and generations of American Indians before them. This hollow, at least part of it, was one such hollow and, for me, the weight of the lives that once inhabited it filled the land. That’s why it was perfect.

As far as what we did with the production design to tell the story of our character, I will say there is nothing too specific, but in the script I believe I described his house as being “sparsely decorated, not necessarily from extreme poverty but more so from lack of need. Yet, the accumulations of a life lived entirely in one place could be found accumulated in the corners and shadows.” There is probably more there, and I hope there is more there in the production design, I hope that the location and character became its own living, organic entity. Every prop and piece of design there results from a choice, inside and out, but it may be belaboring to go into every single one of them!

Mary: I’m a knitter, which some people would say requires patience. I think it’s more about rhythm, and your film develops slowly in small moments. The pace is leisurely, though it seems that at least six months passes in the narrative given our cues from the natural world. And, things slow down as the story progresses in some ways — even the breakfast butter to fry the eggs stops sizzling and the eggs cook just shy of suspended animation. There are reasons for that, of course, but what does this overall choice regarding pace say about you as a storyteller?

Cagney: The choice of pace for Harvest seemed to me the only way to tell the story about life’s routines and the subsequent interruption of those routines. I did not want to simply use poetic language and story structure to communicate this theme; I wanted the audience to feel the theme. For me, the cinema can offer a visceral experience unlike any other medium, as long as the medium is allowed to breathe and avoids the ontological contradiction of plot. My goal was to create a world with a character, who you know has a history, who you know is grappling with issues, and who you recognize in some sort of humanistic way. And, after some time of feeling the repetition and pace of his life, his routine, you feel the force of the interruption.

Mary: We both know that realism is a style, and I have a predilection for it. The music in Harvest — diegetic and non-diegetic — is perfect in its simplicity and ability to evoke place. Visually, the lighting and compositions are beautiful to behold while fitting within the aesthetic frame we think of as realistic. Why these choices?

Cagney: First the music: I approached the musician David Karsten Daniels about doing the score for the film. He is an artist I’ve long admired and he had three very important qualities that invited collaboration. He embraced experimentation; his aesthetic was at times minimalist and at times chaotic but, in either case, the reject rigidity in the form; and, he had, at times, some folk/old time tendencies in his music. The notes between David and me go on for almost eight pages, but in short, I asked him to use instrumentation that feels indigenous but to break it down to its parts, a sort of deconstruction of the sounds of Appalachia. I am so, so pleased with his work for the film. I think the two songs in the film probably speak for themselves. Hazel Dickens’s voice has a gravity unlike any other voice I know–and that is not hyperbole.

Second: the visuals. My cinematographer, Seamus Mulligan-Ferry, and I exist on the same wavelength when it came to the visual design of the film. He has the ability to take the natural world and punch little minutiae of light and shadow that make the real become transcendent. And, in many ways that was what my goal was for this film. It is something Donald Ritchie said about the films of Ozu: He highlighted the seemingly mundane in life until it became transcendent. This is also why there are so many empty frames in Harvest, and why action sometimes leaves the frame yet the frame holds. It is partly a love letter to Ozu, on my behalf, but it also the perfect way to intimate the transcendence of emptiness. In those final frames of emptiness at Hank’s house, you are no longer wondering, “Why is the camera here? Why am I looking at this.” The lack suddenly becomes pregnant with meaning.

Mary: Speaking of the camera, what did you use? The film is gorgeous.

Cagney: RED Epic.

Mary: The meaning in a film rests in individual viewers. For me, Harvest is about change, cycles, and transitions. Everything in Hank’s life starts to go away, the people who connect him to the outside world, his interest in the names he collects, his companion, and that which he harvests. At the same time, others are coming in or are on the edge of doing so. The past and the present are one. The seasons change, and even Hank must make a transition. What is the film about for you, and what do you hope viewers will take with them after seeing it?

Cagney: So, I feel like filmmakers are always obtuse about this question. And, I used to think it was because they were being prickly or stubborn with the press. I mean, I love talking about films so why wouldn’t I want to talk about my own film. But, I think I get it now, after making my first feature. You are right, for me the best cinema holds different meanings for different viewers, and as soon as the author designates a “preferred meaning,” perhaps it loses something. So, even if I did qualify my analysis with the fact that it is just my own feeling, yours may be different, somehow my identifying it lessens it, maybe? Maybe I am wrong. I am happy to talk about process and stylistic choices, which we have done, and which obviously gives some trajectory to the overall meanings. But, specific scenes, pieces of the story, and themes that are up for interpretation. Everybody has different ideas about what he is burning, about what happens at the end, about who his visitor is…I’d rather those remain un-claimed.

Mary: So be it. Thank you, Cagney. Lovely film.